Presenters of Memories and Heritage at the Crossroads at the XII AISU Congress, Palermo 2025.

From 10 to 13 September 2025, Palermo hosted the XII Congress of the Associazione Italiana di Storia Urbana (AISU) – a vibrant international gathering dedicated to exploring the city as a crossroads of relations, exchanges, and cultural encounters.

Among its many panels, Memories and Heritage at the Crossroads, coordinated by Marie-Paule Jungblut (University of Luxembourg) and Rosa Tamborrino (Politecnico di Torino), delved into how urban memory and cultural heritage are shaped – and reshaped – by transformation, resilience, and risk. The presentations took us from Rio de Janeiro’s seaside hotels to Naples’ UNESCO strategies, from Bologna’s innovative “potential atlas” to the fragile recovery of L’Aquila after its earthquake. Together, they revealed heritage not as a static inheritance, but as a contested arena of memory, power, and negotiation.

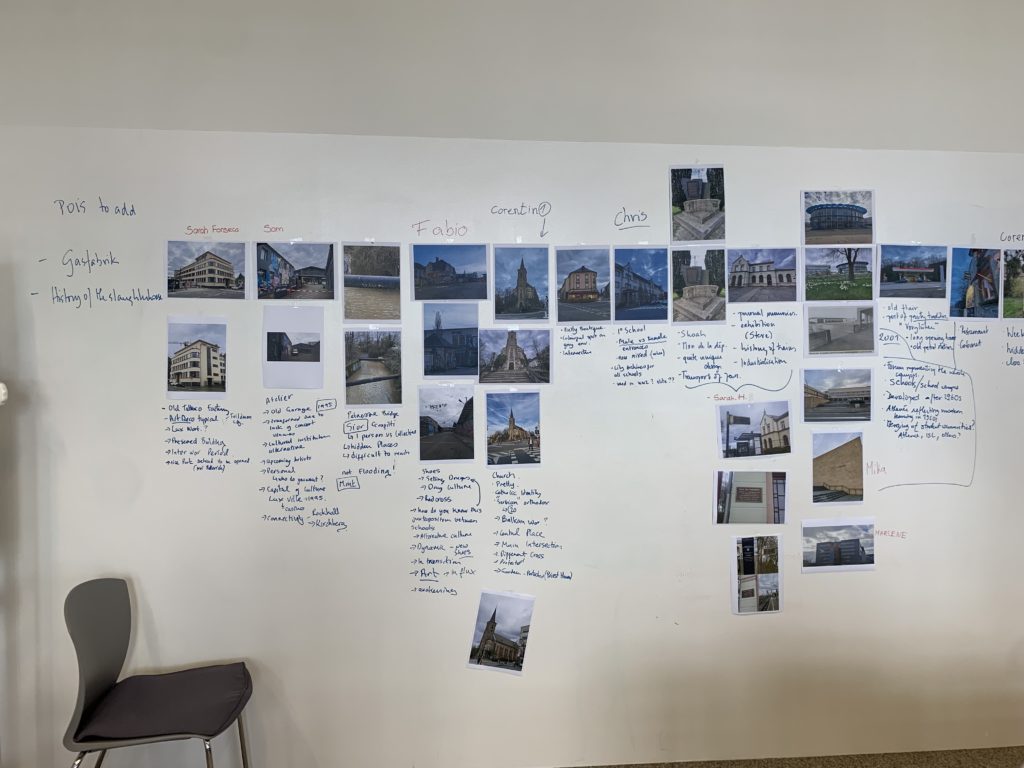

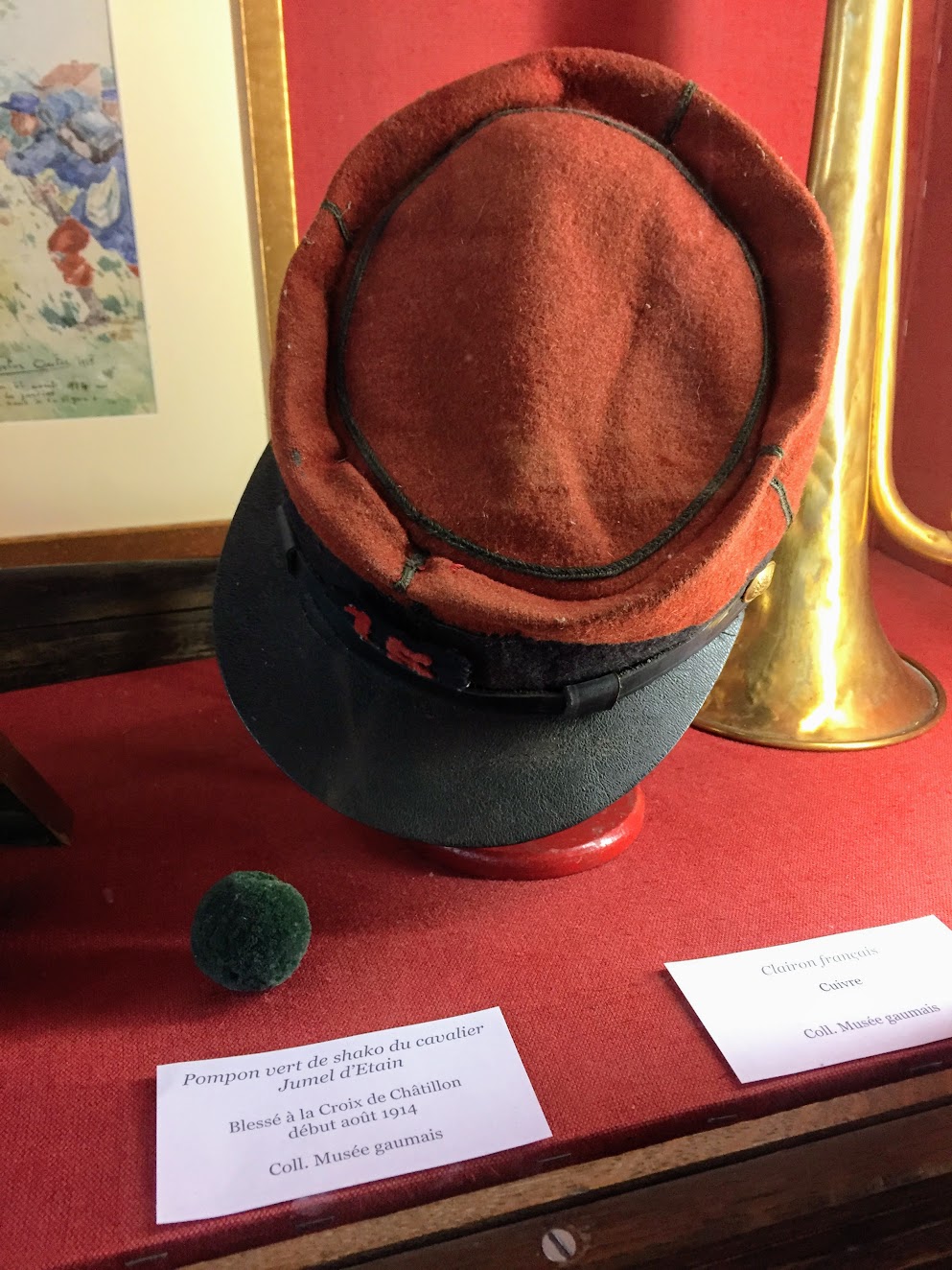

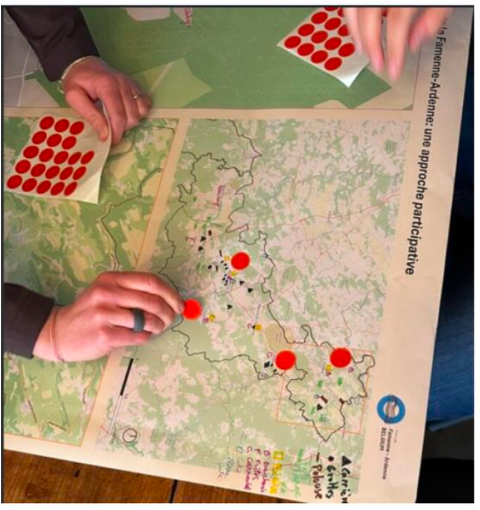

The session highlighted a new approach: heritage is no longer treated only as monumental preservation but as a lived, co-created practice. This resonates strongly with Henri Lefebvre’s theory that the city is not merely a functional space, but a socially produced and lived space – one where meanings are constantly renegotiated. Participatory mapping, storytelling, and community-driven re-significations showed how hidden voices and overlooked spaces can be integrated into broader urban narratives. A vivid example came from the EU-funded RESILIAGE project, which demonstrated how co-mapping and storytelling can reactivate memories, capture cultural practices, and support resilience strategies in cities exposed to environmental and social stress. By funding such projects, the European Union has recognized the urgent need for new, dynamic approaches to heritage that are flexible, inclusive, and future-oriented.

Challenges remain. Heritage is vulnerable – to disasters, commodification, and political appropriation. And while not the central focus of this panel, a new horizon is already visible: the impact of artificial intelligence. AI tools may help recover forgotten memories and unlock archives, yet they also risk flattening complexity and narrowing what counts as heritage. The crucial questions ahead are who builds and governs these systems, and whose stories they preserve – or silence.

At Palermo, AISU reminded us that cities are never neutral: they are lived spaces where memory is negotiated and heritage is fragile. Before the publication of the conference proceedings, there will be a publication of the abstracts, ensuring early access to the contributions. Together, these publications will extend the debates, so that the voices and insights shared in Palermo continue to provoke reflection and dialogue.

Marie-Paule Jungblut, PhD – University of Luxembourg, co-coordinator of Memories and Heritage at the Crossroads, AISU Palermo 2025